The Bat Creek Stone

By Lowell Kirk

The Bat

Creek Stone

By Lowell Kirk

Not Long after I first came to Monroe County in 1969 to work at Hiwassee College several people asked me about the Bat Creek Stone, of which I knew nothing. In 1974 I purchased 12 acres of land on Bat Creek and built a house about 500 feet from the creek, where I still reside. As a teacher of history, I have done a great deal of research on the Cherokee Indian. In 1988 I read an article in the local paper that made a reference to the engraved Bat Creek Stone and Cyrus Gordon’s theory that the was evidence that Hebrews were in Monroe County almost two thousand years ago. A few weeks after that, as I was reading Sara Sands’ History of Monroe County, I ran across the name of Luther Blackman. Blackman was a stone cutter and engraver who operated a marble quarry and stone monument business on Bat Creek.

Blackman was also the postmaster at Marble Hill on Bat Creek in 1857! Suddenly, I made a connection between the “engraved” Bat Creek Stone and Luther Blackman, the stone “engraver.” Could there have been some connection between the two, I asked myself. My first reaction was that this must just be an interesting coincidence, that most likely Blackman was not around 32 years later when the stone was found. But out of curiosity, I began to research the Bat Creek stone.

The Bat Creek Stone was reported to have been found in February, l889 in an Indian mound near the mouth of Bat Creek. John W. Emmert, a Confederate Civil War veteran, working for the Smithsonian, claimed credit for finding the stone and immediately sent it to the Museum, in the belief that the seven “letters” on the small stone were in the Cherokee language. The stone was catalogued and a picture and small reference to the stone appeared in a publication by Cyrus Thomas by l894. Thomas, from Bristol, Tennessee, was directing the archeological for the Smithsonian. Since l960, Cyrus Gordon, a Hebrew scholar, and several other researchers have attempted to prove the stone is evidence that Jews were in America almost 2000 years ago.

My first interest in the story at that point was to prove to myself that the stone “engraver,” Luther Blackman, could not have engraved that stone and focus my research efforts back to Cherokee history. However, I soon learned that Blackman lived in the area until his death in 1919! My curiosity increased. I began to consider the possibility that there was a connection between the Bat Creek “engraved stone” and the Bat Creek stone “engraver.” For the past ten years I have been on an intellectual journey that has been intriguing, and absolutely fascinating! I have come to know Luther Blackman and his thoughts like an old friend, with much thanks to his grand-daughter, Mrs. Glen Davis. I have trudged through valleys and mountains of history that involve Native Americans, Hebrews, Mormons, Melungeons, and Cherokee. I have waded through Civil War and Reconstruction, Mississippian Mound builders, the early history of the Smithsonian Institute, President Grover Cleveland’s first administration and Benjamin Harrison’s election and inauguration. I delved deeply into the national political controversy between the Republican and Democratic political parties in the late l9th century. I have become familiar with the great disruption caused by the Civil War and Reconstruction in East Tennessee and into and lots of Nineteenth Century Monroe County history. I have uncovered many myths and myth builders, and myth demolishers. I followed many dead-end trails, and had to backtrack to the main trail that led to the solution to the puzzle of the origin of the Bat Creek Stone. And all along the way I made many new friends and acquaintances.

Luther Meade Blackman

The two primary players in this story of intrigue and mystery are Luther Meade Blackman and John W. Emmert. Blackman was an absolutely brilliant, highly educated man, Civil War officer and prominent Republican who was much molded by his hatred of Rebels and Democrats. Blackman was born in Connecticut and educated in Michigan. He came to Knoxville 1855 as a letterer and engraver for a monument company. In l857 he moved to Bat Creek to operate a monument business. In l890, he was still in the monument business as well as being a Federal Claims Commissioner and leader of Monroe County Republicans.

Emmert was a relatively uneducated, obscure former Confederate Army private from Bristol, Tennessee and life-long Democrat who was employed in l884 by the Smithsonian to dig in Indian mounds in what was a successful attempt to prove that the Mound builders were not descendants of the lost Tribe of Israel. That theory was the prevailing belief in the Nineteenth Century. Old myths die hard. There are many, including Mormons, who still cling to it. Some of these believers use the Bat Creek Stone to support their belief.

Those who have believed the Bat Creek Stone to be a forgery of fraud, include Dr. Charles Faulkner, anthropologist at the University of Tennessee and Jefferson Chapman, Director of the U.T. McClung Museum. They believe that Emmert perpetrated the fraud. My researches indicate that Emmert himself, was a victim of the fraud, set up to send in a fraudulent engraved stone so he would get fired, for the second time.

Supporting players in my story John Wesley Powell, a key founder of the Smithsonian, and Cyrus Thomas, who directed the archaeological work. By l890, Thomas proved that the Mound-builders were Native Americans and not the Lost Tribe of Israel. Like John W. Emmert, Cyrus Thomas was born and raised in Bristol. Other supporting players include John P. Rogan, “scoundrel” and cousin of Cyrus Thomas who lost his job with Thomas in l886 and became a Bristol bookseller. Others include L.C. Houk, from Sevier County, who controlled the Tennessee state Republican political machine in the l880s, Grover Cleveland, President of the United States, who in the spirit of the l883 Pendleton Act, tried to clean up the corruption in the U.S. Postal Service and Pension Claims offices. Blackman worked as a Pension Claims Agent from l870 to l890. However, President Cleveland allowed most Republican’s who held Federal patronage jobs in East Tennessee to be replaced by Democrats by l886. In l889, Republicans in East Tennessee were out to get all Democrats fired from Federal jobs.

As I was engaged in my Bat Creek Stone research, always in the back of my mind was the hope that as I kept pursuing this “mystery,” that I would find some concrete evidence that Blackman was not involved, so that I could get my mind and time back on my Cherokee researches. Not one single piece of concrete evidence has excluded Blackman as the perpetrator of the Bat Creek Stone; and virtually every avenue I have pursued has added evidence that Blackman engraved the stone. He had the knowledge, skill, opportunity and extremely strong motive. by a letter written by his

own hand, has proven himself to have been on the spot when the deed was done. He was intimately familiar with the U.S. Department of the Interior, of which the Smithsonian was a part. The circumstantial evidence pointing to Blackman is overwhelming.

The efforts of J. Justin McCulloch as published in a l988 article in the Tennessee Anthropologist, “The Bat Creek Inscription: Cherokee or Hebrew?” includes a large number of pieces of this puzzle. But McCulloch has not put all of them together in the right place. McCulloch is correct that the inscription is composed of ancient ”Hebrew” letters. But Chapman and Faulkner are correct in that the inscription is a skillful forgery done in the l9th Century! McCulloch wrote, “If one insists on making the Bat Creek inscription a forgery, one could easily find far more plausible culprits than Emmert.” Although it has not been easy, I have done that! What I have added to the puzzle is the man, the motive, the opportunity and the broad and complicated outline or border of the puzzle. it was the intricate and complicated was of a variety of nineteenth century developments that make up this border. When one stands back and looks at all the center of the puzzle of the Bat Creek Stone. And at the center is Major Luther Meade Blackman.

Blackman set John W. Emmert up to get him fired from his job by sending in a fake stone. J. Emmert was a Democrat who had been hired after Grover Cleveland and the Democrats took over the national government in l885. Emmert was an old acquaintance of Cyrus Thomas. Both were from Bristol, Tennessee. Emmert's leg had been badly wounded in the Battle of Drury’s Bluff in May of l864. In l885 he was disabled and badly needed a job. Although Republicans controlled East Tennessee, Democrats controlled the Federal government and fired most Republicans in Federal patronage jobs in East Tennessee after l885. Emmert worked in Monroe county digging in Indian mounds in l886-87 along the Little Tennessee River and at Tellico. He also worked on mounds at Cog Hill and the Hiwassee River mounds in McMinn County. In l888 East Tennessee Republicans got him fired from his job on the Democratic Senator from Tennessee and his Republican friends in Bristol, President Grover Cleveland himself ordered an investigation in Washington which cleared Emmert. Emmert was rehired in January l889 and began digging again in Monroe County at the mouth of Bat Creek. During that time he resided in Morganton, just across the river from the mouth of Bat Creek.

When Emmert showed up in Luther Blackman’s back yard, Blackman was determined to get the old Confederate Democrat fired again, this time young local teenage boys that Emmert had hired to do the actual digging, as he was himself disabled. They gave it to Emmert, who claimed to have found it himself. One of those teenage boys was Jim Lawson, son of Blackman’s neighbor. I suspect that Blackman’s own son, who was a blacksmith, also assisted in the l889 dig in the Bat Creek Mounds.

The Bat Creek Stone

Courtesy of Tennessee Anthropological Association

Once the engraved stone was in Emmert's hands, local Republicans tried to get Emmert to send the stone to Knoxville to have it “translated.” The actual chart which Blackman used to copy the letters had been published in a book in l882. According to the chart which Blackman used to carve the stone, the translation would have read, reading from right to left as Hebrew was, “QM, LIES.” QM referred to Blackman’s position as Quartermaster of the Fourth Tennessee Union Cavalry in the Civil War. Emmert, of course, immediately sent the stone to Cyrus Thomas, never allowing a local "translation".

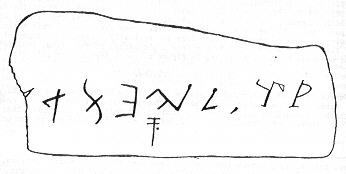

Copy of a Drawing of the Inscription by Emmert

In l889 Blackman was the Monroe County leader of the L.C. Houk political machine in East Tennessee. The Houk machine controlled all Republican patronage in the First, Second and Third Tennessee Congressional Districts. One of the many complications to this puzzle was that the Republicans in the First District (Chattanooga) were in the process of stripping the Houk political machine in Knoxville of appointment power in their districts. The Houk machine was made up of old “Radicals” who were still engaging in “Bloody-Shirt” politics and carrying on the political aims of “Radical Reconstruction” politics. Those First District Republicans had given support to help Emmett get his job back after he had been fired in l887. Blacken, by getting Emmett fired for sending in a “fraudulent” stone, would also help discredit Hook’s enemies in the republican party in East Tennessee. That failed. By l892, the Hook Machine and the old Radicals and their “Bloody Shirt” politics were out of power.

All of this was never exposed at the time for an obvious reason. The stone was reported found February l4, l889. The Republican President Benjamin Harrison was inaugurated president on March 4. (Blacken went to the inauguration.) Harrison immediately began the process of removing all Democrats from Federal patronage jobs. So Emmett was removed from his job, without the stone. Syrups Thomas, who knew that stone was a fraud, simply “stonewalled by putting it in a drawer at the Smithsonian and never mentioning it again. If Thomas had made an issue of it, that could have gotten him fired. And so the stone lay undisturbed in the Smithsonian until about l960, when Hebrew scholars have attempted to prove it a genuine 2000 year old artifact.

The full outline of this story simply cannot be told in a short article. But the primary point to be remembered here, is that the Bat Creek Stone was a clever forgery, perpetrated for political reasons. If there were Hebrews in Monroe county 2000 years ago, they did not engrave the Bat Creek Stone. Luther Blackman did it in l889.

Home...The Tellico Plains Mountain Press

Copyrighted - All Rights Reserved