Copper was discovered there in 1843.

This discovery would impact the lives of Copper Basin residents for generations. Population growth, land

speculation, numerous mine openings and other related activities led to the boom of the area by the early

1850’s. However, no one knew that the state-of-the-art technology being used at that time to

process copper would have devastating effects on the

environment. In fact, the devastation was so great the

Copper Basin was once considered the largest man-made

biological desert in the nation. Over 50 square miles

(32,000 acres) was stripped of vegetation resulting in mounds

of soil being washed away with each rainfall. Sulfuric

acid fumes filled the bowl-like topography and led to the

nation’s first look at the long-term effects of acid

rain.

The Ducktown Basin, or Copper Basin,

is located in the extreme southeast corner of Polk County,

Tennessee. Three veins of copper run through the basin

and each attracted several mining companies ready to

exploit the resource.

The early inhabitants of the Basin

were Cherokee Indian farmers who were hunters and produced

some copper. By the Treaty of New Echota in 1836 they

gave up many of their lands, including those in the Copper

Basin. Many of the Indians who remained in the Basin

after the treaty were removed by the U.S. Army in 1838 during

the Trail of Tears.

Because there were no roads into the

Basin, settlement was slow to occur. The first white

settlers came to the area to farm, but until 1839 there

was little white settlement. That year, prices

were lowered from the starting price of $7.50 an acre, which

had been established when the land was surveyed after the

Indian Removal, to only $l an acre. The farming community of

Pleasant Hill was founded around 1840 east of present-day Copperhill, the first organized settlement in the Basin.

The lack of roads into the Basin

increased its isolation and prevented economical shipment of goods outside the Basin and helped retain an agricultural

lifestyle. The earliest recorded shipment of copper out of the

Basin occurred in 1847 when shipped, by mule, 90 casks of

copper to Dalton, Georgia, the nearest railroad. It was shipped north of

the Revere Smelting Works near Boston.

In 1851, the Copper Road between

Hiwassee and Cleveland began to be constructed in Bradley County and was completed in 1853. Now copper could be

taken economically by copper haulers to Cleveland for shipment, and other goods could be brought back

into the Basin. Copper haulers would make this journey in two days, spending the night at a

halfway house. On the return trip from Cleveland the

wagons were usually loaded with merchandise for the stores,

and with mining supplies. The original road was used

throughout the 1800s as the only way to ship copper out of

the Basin. (The road route was later used for part of

U.S. Hwy. 64.)

In 1857 only five mines were

operating regularly -- the Tennessee, Mary’s, Isabella,

Eureka, and Hiwassee. In 1858 the mines in the Basin

began to consolidate into three large companies -- the Union

Consolidated Mining Company, the Burra Burra Copper Company,

and the Ducktown Copper Company.

The Civil War disrupted work at the

mines, as the miners left to fight in the war and the mines closed down. Many mine interests and smelting plants

were owned by northern industrialists who closed the mines in late 1861. The confederacy gained

control of the Basin in 1863 and sold the mines to southern

capitalists to provide the south with needed copper.

The mines were operated at a reduced capacity through the end

of 1863 when Federal troops again gained control of the

area. After the Civil War the miners and their families

returned, the damage to the mines was repaired, and mines

reopened. The Burra Burra and Union Mines were reopened

in 1866, the first to do so.

The Copper Basin’s ore is three

deep seams and could only be extracted by deep shaft mining,

a dangerous activity. Dynamite charges used to loosen

ore could cause cave-ins and many miners lost their lives in

the mines.

In the late 1870s most of the mining

companies in the Basin began to fail because of a lack of

adequate transportation and decreasing quality of ore.

The cost of transporting the ore would have been greatly

reduced by rail. Without rail transportation it became

uneconomical to ship copper.

The copper mines in the Basin were

idle for more than ten years until the Marietta and North Georgia Railroad built a spur line north to the area.

The arrival of the railroad ended the isolation of the Basin and made transportation of people and products

easier.

The Georgia spur was met soon

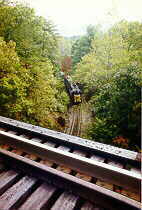

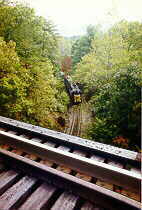

by the spur from upper Tennessee. The major obstacle in

the Tennessee line was the Hiwassee River gorge, with a 426-foot

difference in the height between the north and south shores of the river. George Eager of

the Knoxville Southern Railroad designed a switchback to eliminate the obstacle. The switchback

was located near Farner, Polk County, Tennessee. The completed rail resembled a “W”

built up the river gorge.

These two lines consolidated in 1890

as the Marietta & North Georgia Railroad. It passed

into receivership in 1891 and was reorganized in 1895 as the

Atlantic, Knoxville, and Northern Railroad Construction Company (AK&N). In 1896 it was finally

incorporated and began to run the rail line.

In 1890 the Ducktown Sulphur, Copper

and Iron Company (DSC&I) of London, England, re-opened the Mary mine and built a furnace with a l00-ton-a-day

smelting capacity.

In 189l the open roast heap smelting

process of copper was begun. This process, and the high

sulfur content in Polk County copper, created sulfuric acid

fumes which, combined with the timber cut as fuel, destroyed

vegetation in the Basin.

They replaced the cumbersome

switchback at the Hiwassee Gorge with a loop around Bald Mountain in the gorge. The loop was necessary because a

train could pull only three or four cars up the

switchback, and a pusher train was needed to help get the

trains up. This was very time consuming at a time when

the line was getting more traffic. T.A. Aber, a civil

engineer with the Louisville and Nashville Railroad, designed

a loop around Bald Mountain, in the middle of the Hiwassee

River, to eliminate the switchback. The loop, over

8,000 feet long, would circle the mountain one and a half

times up a passable grade until it reached the plateau height

near Farner north of Ducktown. Trains began running

over the loop in 1898 and continue to do so today.

By 1899 the Tennessee Copper Company

had bought or leased mines from most of the other mining

companies in the Basin. They built a new smelter in

McCays (renamed Copperhill) and built a railroad between

Ducktown and the smelter. They began a new mine, the

Burra Burra near the Hiwassee Mine site.

Two lawsuits involving the Basin

Copper industry occurred at this time in 1904 by landowners. Tennessee courts ruled that the value of the copper

companies’ contributions to the county out-weighed damages they caused. Before the copper industry

came to the area, there were only around 200 residents.

The court noted that, at that time, the open-roast heap

method of smelting was the only known smelting method.

In 1906 in Georgia vs.

Tennessee Copper Company, the Supreme Court heard

Georgia’s claim that TCC was taking away its sovereign rights of control over

its land and air. Georgia was seeking an injunction

preventing TCC from using the open roast heap method.

The Court found for Georgia but did not issue the injunction

because by then TCC had begun construction of an acid

reclamation plant near Copperhill. Eventually, sulfuric

acid replaced copper as the company’s major product.

Within two decades of the ruling the

first efforts would be made to reclaim the barren landscape. Those efforts would continue into the 1990’s.

Once looking more like Mars

than East Tennessee. Over 50

Sq. miles were stripped

of vegetation

Another technological

advancement which occurred in the Basin was a way to extract

iron compounds from the copper ore. This allowed the companies to

retrieve iron, copper and sulfuric acid from the mines.

Reforestation efforts began in the

1920s and 1930s and concentrated efforts began in the 1940s.

Early efforts were carried out by the mining companies and

TVA. Hundreds of acres of pine were planted between

1939 and 1944.

In 1941 the TVA established a

CCC camp in the Basin to enhance their tree planting

efforts. The CCC workers built dams, planted trees, and

covered the ground with straw to prevent runoff. Six-

teen buildings existed in 1941; all that remains are ruins of

some foundations and leveled sites where the buildings stood.

Later owners of the copper mines and

acid production facilities were Cities Service and Tennessee

Chemical Company. Throughout the 1980s, the vast

company land holdings began to be sold off. In 1987,

the copper mines were closed and sulfur was brought in by

rail for acid production. Tennessee Chemical Company

filed for bankruptcy. The production facilities were

purchased by Boliden Intertrade AG, a Swiss company, and

renamed B.I.T. Manufacturing.

The Burra Burra Mine Pit today...Notice the

Reclamation

Efforts

Have proven to be Successful. The Goal is to Have

Complete

Reclamation by the Year 2000.