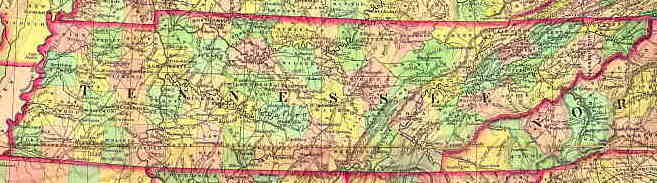

1814 Map Of East Tennessee

TENNESSEE

The Origin of Our State's Name

By Bill Baker

Tennessee. Ten-nes-see. Did you ever wonder about those three syllables? Those three syllables that represent to the world, that long green swath of God's earth, stretching from the ancient peaks of the Appalachian Mountain Chain to the great convergence of waters draining from America's heartland, the Mississippi River. Where did that word come from? What does it mean? And, how did our State come to be called Tennessee?

As most everyone knows, the word Tennessee, is of Native American origin. The first historical record concerning the word form was left by the expedition of the Spanish explorer, Captain Juan Pardo. In the summer of 1567 he left his base on the coast of present-day South Carolina and traveled inland with a detachment of soldiers. Pardo and his men passed through numerous Native American villages along the way, noting their names as they went. Somewhere during their trek, the Spaniards happened upon a village called ... "Tanasqui".

The exact location of the town of Tanasqui, which Pardo visited, and the tribe, to whom it belonged, is uncertain. But, from the narratives left by a few of his men concerning the distances marched, the courses of the rivers, and a mention of traveling of along the mountains", it would appear to be in Cherokee country. The Tanasqui-Tennessee word form was also the name of two Cherokee towns which existed in later historical times: one on the Hiwassee River in what is now Polk County, TN. and the other on the Little Tennessee River in present-day Monroe County, TN. Our State's name was borne from the latter.

The Cherokee had some contact with the seacoast based Spaniards over the next century and a half after Pardo's visit, but due to the distance between them, and the hazards of crossing the territory of their enemies, the Creek and Catawbas, that contact was limited. The Europeans did not have much of an effect upon Cherokee culture until the early 1700's, after the English colonies of Virginia and South Carolina had became well established. Fur traders from these two colonies began probing deeper into the Appalachian frontier to barter with the Cherokee for pelts. Over a period of a few decades, the English traders came to be a common sight in their villages, and, the Cherokee began acquiring their first muskets. Pack trains laden with trade goods, deerskins, and furs of all kinds, tramped back and forth on the wilderness trails between the Atlantic Coast colonies and the Cherokee towns with ever increasing regularity. .

During this same era, France began trying to expand its holdings and influence southward from Canada, and to the north from the Gulf Coast. The English colonists, who were scattered along the Atlantic seaboard and westward towards the Appalachians, became uneasy. They had no desire to see their old rivals in war and commerce set up camp in their back yard. England and France both realized the wealth potential of the forests and river valleys which lay just beyond their colonial frontiers, and also, the necessity of having the red man as an ally if that wealth were to be harvested. These two global powers became slowly entangled in a struggle for the vast North American interior, which eventually culminated in the French and Indian War (1756-1763). The Cherokee were caught in the middle, with England and France both vying for their allegiance. In the span of a few decades, the Ani-Yunwiya, as the Cherokee called themselves, went from being a tribe of isolated mountaineers, to players in the theater of world events.

In 1714 the French built Fort Toulouse on the Coosa River in the Alabama country, near the present-day town of Montgomery. From there they began asserting influence on the Cherokee known as the "Overhills", which were that part of the tribe living on the Hiwassee, Tellico, and lower Little Tennessee rivers. (Note: Prior to an official resolution in 1819, the river known today as the Little Tennessee, was commonly called the "Cherakee River", or, the "Tennasee River".) The English became increasingly alarmed, for the Overhill Cherokee were the most warlike division of their nation. If they remained as allies of the English, they would act as a comfortable buffer between the Atlantic Coast colonies and the French threat looming on the western frontier. If they went over to the French interest, the English would no doubt suffer some dire consequences. Three things were greatly dependent upon the alliance of this particular Cherokee as far as the English were concerned: the future control of the North American interior, the fur trade, and the assurance that Cherokee warriors under French influence would not threaten England's colonies.

In a letter to Governor James Glen of the colony of South Carolina, Ludovic Grant, a Scottish trader living among the Cherokee, warned what would happen should the French gain favor over the English with regard to the Overhills. He bluntly pointed out the power and influence which the overhill towns held within the Cherokee Nation when he wrote ... "If the enemy once gets possession of the Overhill Indians, all others will quickly submit to save their lives."

The English had always found it frustratingly difficult to deal with the Cherokee on a diplomatic level however, because their tribal government did not function like that of the Europeans. The Cherokee Nation was divided into three geographical divisions: the Lower, Middle-Valley, and overhill Towns. These groupings of towns were spread out over a vast area, from the present-day regions of northern Georgia and northwestern South Carolina, up through the corner of southwestern North Carolina, and across the mountains into east Tennessee. Each of these provinces had a headman or a small group of elders that represented them in their affairs, but, they had little power to actually make policy, and the populace often ignored their decisions. Captain Raymond Demere, the first commander of Fort Loudoun, a British garrison constructed on the Little Tennessee River during the French and Indian War, explained it best:

"The Savages are an odd Kind of People; as there is no Law nor Subjection amongst them, they can't be compelled to do anything nor oblige them to embrace any Party except they please. The very lowest of them thinks himself as great and as high as any of the Rest ... but every one is his own Master"

The problem was: how to deal with a large nation of people that did not grant their leaders any power over the individuals of that nation, where every person was ... "his own Master". In an effort to centralize the Cherokee government and make it more like their own, the English had often tried to coerce the tribe into choosing a single headman as their supreme ruler and chief diplomat. In 1716, the Conjurer of Tugalo was appointed to the post, but his "reign" eventually piddled out. Other "kings" followed, with the same results... much to the frustration of the English. The Cherokee just wouldn't play by the white man's rules.

During the early 1720's, the Warrior of Tannassy came to be recognized by his people as the principal headman of the Overhill towns. Seizing an opportunity, English emissaries wooed the Warrior. They knew good and well that a vigorous trade with the Overhills, coupled with a close diplomatic relationship with their most powerful war chief, would pretty much sway the whole Cherokee Nation to their favor ... and ruin any plans that the French might have for luring the tribe into their fold. Subsequently, during the next several years diplomacy was focused upon the Warrior's village, which lay at the western foot of the Appalachians, on a horseshoe bend of the Little Tennessee River. Documents, maps, and letters referring to the land of the Overhill Cherokee, gradually began noting it as the country of Tannassy, although, with an amazing number of different spellings. Here are some of those and other various spellings, as found on old maps and in early historical records: Tennassee Tunasse Tanase Tunesee Tonice Tinnase Tannassy Tennasse Tanasee Tannassie Tannessee Tannasie Tenessee Tenesay Tenasi Tanasi Tunissee Tenase Tanasqui Tenesee Tanisee Tanesi Tunese Tinassee Tunnissee Tennisee Tennesy Tennecy Tunassee Tennasee Tanassee.

It is believed that James Glen, the Governor of South Carolina, was the author of our modern day spelling, T-e-n-n-e-s-s-e-e, for he used it in his official correspondence during the 1750's. And supposedly, according to popular tradition, it was Andrew Jackson who proposed that our State be named Tennessee when it joined the Union in 1796. However, it is a matter of public record that the secretary of the old Southwest Territory, Daniel Smith, who submitted the first draft of the constitution for the formation of the new state, officially committed to paper in the preamble of that document: "by the name of the State of Tennessee."

As for the meaning of the word Tennessee...

There are some that say it is lost to the ages. Others say that it means "big spoon" ... but this translation is very doubtful. The exact meaning can probably never be proven with absolute ironclad certainty, due to the fact that the knowledge of the precise dialectal source has vanished with the passage of time. Also, some of the smaller and less well-known aboriginal peoples of the old Southeast are now extinct and their languages ceased to exist long ago. However, there is one very probable translation.

The word Tennessee is thought to be the Cherokee variant of a Creek word the pronunciation of which was probably corrupted by the first whites. When the Cherokee first began settling in the lower Little Tennessee Valley, they inhabited sites formerly occupied by the people of the Creek Nation. There are several location names in the Cherokee country that are of the Creek language and are reminders of their former presence there. Tallassee and Tomotley were two Cherokee villages on the lower Little Tennessee River that bore names of Creek origin, and most likely the Cherokee town of Tannassy was built upon the site of a former Creek settlement, with the Cherokee using the same name for the site as did their predecessors.

Some have proposed that Tennessee is a Yuchi word that means "meeting place". According to an ancient Cherokee tradition, there was once a small settlement of Yuchi (or, Uchee) who occupied the area around the mouth of the Hiwassee River, in close proximity to the Overhill towns. It should be noted here also, that in that same area, one of the villages bearing the Tanasqui-Tennessee name was located. The Yuchi had their own separate dialect, yet most of them were said to have spoken Creek and Cherokee as well. In latter historical times they merged with the Creeks. Therefore, if Tennessee is a Yuchi word, it wouldn't be incorrect to say that it is a Creek word also, as formerly stated, because the Yuchi were one of the many tribes, which made up the Creek Confederacy.

A former Justice of the Supreme Court of Tennessee and President of the East Tennessee Historical Society, Samuel Cole Williams, wrote several of the most thoroughly researched and definitive books on the subject of Tennessee history ever published. An authority on the Cherokee dialect whose opinion Mr. Williams respected, once translated the meaning of Tennessee as, "the bends" ... which would undoubtedly mean the "bends" of a river. This would seem to conflict with the Yuchi translation of "meeting place". But, think of a river bending until it almost comes back to meet itself... then, the translations have a very similar meaning.

It should also be noted that a word in the Cherokee language that ends with the suffix-vowel sound, ee or yi, is usually locative, the ee sound meaning If place", in much the same way the suffixes ville or burg would denote a town in modern English. Therefore, Tenness, when coupled with the suffix, ee, would undoubtedly mean: "the bends place". The Cherokee language is notorious for its references to happenings or implied vagaries that only a well-informed person of that culture would understand. To illustrate this point, consider the word: Uniyahitunyi - "Where They Shot It" ... which doesn't say exactly what was shot or who "shot it", or... Degalgunyi - "Where They Are Piled Up" ... which doesn't say what is "piled up", but is the name of a place on the Cheowa River where there are several ancient rock cairns. Likewise, the translation, The Bends Place, is also somewhat vague, in that it doesn't specify what "bends". The English translation in a more direct sense would be: The Place Where The River Bends.

If one had ever stood upon the site of the old village of Tannassy on the Little Tennessee River, they would have plainly seen that The Place Where The River Bends was quite an appropriate name for that particular spot. Before the waters of Tellico Lake flooded the site in the fall of 1979, the Little Tennessee River flowed by old Tannassy in a wide curving arch, almost exactly like a horseshoe.

Before the river's impoundment an attempt was made to locate the archaeological remains of Tannassy. In 1762, Lt. Henry Timberlake, a British soldier, drew a map of the area, which was incredibly accurate. It proved to be an invaluable aid to archaeologists in locating the sites of Cherokee towns on the Little "T". Chota, a large town just upstream from Tannassy, had been under excavation for a few years when the attempt to find Tannassy was made. Timberlake's map showed a small creek [Rocky Holler Branch] separating Chota and Tannassy. Although the lower end of Chota had proven to be thickly settled, with layers of occupation overlapping, nothing could be found where the town of Tannassy should have been. But, there was a clue that quite possibly explains Tannassy's strange disappearance.

From historical records it is known that Chota and Tannassy were originally two separate towns, with Tannassy being the most significant in the first few decades of the 1700's. But, during the latter half of the century the population of Chota grew until Tannassy was little more than a suburb of it. Timberlake's map clearly shows a large difference in the size of the two towns as he saw them in 1762. In records and eyewitness accounts from the era of the American Revolution, 15 to 20 years after Timberlake's visit, there is scarcely, if any, mention of Tannassy.

The topsoil covering the Chota site was very rich and loamy, while the topsoil at the Tannassy site, just over on the downriver side of Rocky Holler Branch, was extremely sandy. According to locals, during an unusually big flood in the 1960's, the field in the bend of the river where old Tannassy had once stood was seen to be covered with water, while most of the Chota site remained above the flood plain. Therefore, a very likely explanation for Tannassy's static population growth, is that the site was susceptible to flooding, and Chota was not. This would also explain the sandy topsoil and lack of any evidence of occupation at all. over the passing years, during widely interspersed times of uncommonly heavy flooding, Tannassy was simply washed away.

A lone monument now stands on the shores of Tellico Lake. Its inscriptions, etched in stone, are the only physical evidence to be seen of Tannassy's existence today. But, all over the world, everyday, when somebody says the word Tennessee, it harkens back to this now quiet and lonesome spot... where proud warriors of the Cherokee Nation, once sat in council with the emissaries of Europe's most powerful countries.

1834 Map Of Tennessee

The Tellico Plains Mountain Press